Megaoesophagus - Atlas of swine pathology

Where: digestive system

Possible causes: Gastric ulcersOther

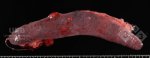

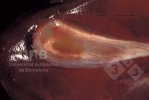

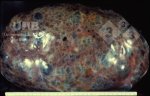

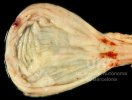

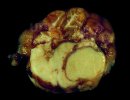

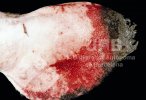

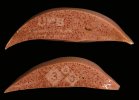

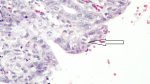

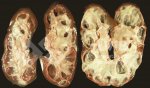

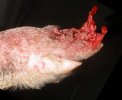

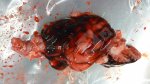

Megaesophagus is characterized by dilation and general increase in size of the esophagus, absence of peristalsis, presence of tertiary contractions and partial or total inability of the gastroesophageal sphincter to relax. These changes could lead to dysphagia that, consequently could compromise the pig’s nutritional state. In addition to regurgitation and weight loss, coughing, mucoid and purulent nasal discharge, as well as dyspnea with pneumonia due to concomitant aspiration may be observed. Regurgitation at variable frequencies and weight loss are among the clinical signs observed in the animal. The diagnosis made for these animals was based on observation of clinical signs and post-mortem examinations. Post-mortem examinations of all pigs revealed ulceration of the pars esophagea of the stomach. When the ulcer heals, it leads to scarring or, in severe cases, to strictures, as seen in these cases. The stenosis of the esophageal opening appears as a rigid ring, and the opening can become so small that pigs often vomit after eating, as seen in this case. Different factors contribute to the ulceration of the stomach. These could be infectious, nutritional, behavioral and/or management-related factors.

Treatment in cases like this are usually supportive or surgical procedures. Supportive treatment is characterized by changes to animal management practices, in addition to the utilization of drugs such as antibiotics, prokinetics, and antacids. Surgical methods can be performed using several techniques, such as the esophagus-diaphragmatic cardioplasty, or Heller myotomy, associated with fundoplication (none of these are practical in a farm setting). Some animals with congenital idiopathic megaesophagus are able to recover on their own while the acquired condition is irreversible. In regards to secondary megaesophagus, once the cause of the problem is resolved, the animal has a chance of recovering.