What is diagnosis? Diagnosis is understanding the cause of disease. Most of the swine diseases and conditions are multifactorial, so there can be one or several bacteria and/or viruses involved, as well as factors from the living conditions of the pigs: environmental, nutritional and management factors.

A diagnosis will help us understand which of these factors are the most important and if we understand the cause of the disease, we know what to do.

Case history

The first step is to get a case history: What is actually happening and what are the goals of the farm?

Farm background information:

- Size of the herd. What kind of animals do they have? From where are they getting their animals?

- What are the people doing?

- What signs are observed in the pigs? Were they coughing? Were they eating?

- What are the farm records telling us?

The farm visit is a basic step still (Figure 1). We need to go there and see what's going on. We can get videos, photos, and data, but whenever you visit the farm, you find out things that staff won't tell you- maybe because they didn't think it was important or worth for the vet to know, or sometimes there are things that people really want to hide. Other times people may be unaware of issues.

Do a walk-through of the farm to practice observation and examination. Stop speaking and listen to the pigs. Learn how to look at the pigs and train your eyes. It is important to look at every one of them. I tell people they need to look every pig in the eyes.

What is their body condition? How is the amount of gut fill? Sometimes the gut is big but the body condition is poor. Look at the feeders: Are they clogged or leaking feed? Is there feed consumption? Feed wastage? What's in the feeder?

What is the rectal temperature? The normal temperature of a healthy pig from birth until several months of age is going to be pretty much around 39.2℃.

Always carry a marker and mark the pigs that you may want to recheck or have as necropsy candidates. Do not trust your memory or the staff’s memory to locate those pigs. Write down which barn or pen where those animals were.

What do you smell? What do you feel? The way your clothes hang on your body will tell you about the relative humidity.

Taste also provides information. In a customer farm, sows were not eating. We found out by tasting the feed that it was terribly bitter as somebody was dumping tilmicosin on top of the feed.

Invasive examinations include necropsy, blood collection, or slaughter checks.

The necropsy rate depends on the herd: some farms will open any pig if they didn't know for sure what the cause of death was.

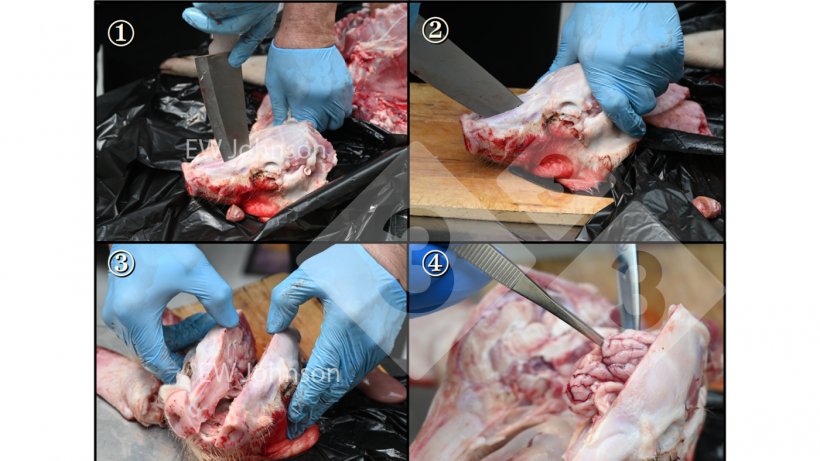

To do a necropsy for diagnostic purposes:

- Select some pigs with a fever (greater than or equal to 39.7) and sacrifice them. Pigs marked during the visit could be candidates.

- Dead pigs are not so useful. Often they are in poor condition and have been suffering from chronic illness.

- You need a solid, cleanable surface, a sharp boning knife (not a scalpel blade), gloves and if collecting samples: bags, alcohol and a lighter.

- Order and hygiene are crucial:

- Open the thorax first to make sure to get the lungs without contamination

- then the brain

- and then the gut, and in that order.

If you have been examining the gut first, you are going to find whatever's in the gut in all the other tissues.

Sample collection: Every sample must go in a separate bag to avoid cross contamination. Collection must be done carefully and alcohol and a lighter will be used to flame the instruments.

For histopathology fix the tissues in formalin: 10% formalin (1 part formalin in 9 parts water). If formalin is not available, you can use anything higher than 70% ethanol to get the fixation started and then the tissue can be refixed at the laboratory. It is not perfect but it's better than nothing and it is better than not getting any samples at all.

Take small pieces for fixation (not more than 2 cm in diameter). Flush the gut with formalin or ethanol so the villi are well fixed.

Consider where to take the sample according to the problem: If you're having an E. coli problem keep in mind that the E. coli causing the problem is in the jejunum, not in the colon, therefore rectal swabs are not the sample of choice and can provide misleading information.

Shipping the samples to the lab

Consider how long it will take to reach the lab. Separate fixed and fresh tissues. Freeze PCR samples if possible. Avoid the use of glass that can break and ice cubes that will melt. Use ice packs or frozen water bottles. Wrap up the cooling material with paper or put it in a bag to avoid condensation leaking.

Histopathology

Histopathology extends what you can see with your eye. It helps interpret the results of other tests and it can also often give us the diagnosis.

The process of preparing the samples for histopathology used to take several days, but it can be done in 4 hours now if needed.

Sometimes we can find things that we didn't expect to see. (Figure 3)

Bacteriology

Bacteria are cultured for two main reasons:

- To identify the bacteria and get a sensitivity test to help select the antibiotic to be used.

- To make the bacteria available for the preparation of autogenous bacterins.

PCR and ELISA, are very popular and excellent diagnostic tools. PCR can detect the presence of a potential pathogen. The ELISA test can find out what the animal antibody level is. The antibody level is the animal´s response to a vaccine or a pathogen.

These are indeed just simply diagnostic tests; they do not tell us why the pigs are sick. They are pieces of information but they are not the diagnosis. Sometimes you can get the diagnosis from a single test, but typically we gather the information and we integrate it to get the diagnosis.

The vet needs to step back and watch what's going on. We need to get data, turn that data into real information and then turn the information into a solid diagnosis. Then finally we take some action, evaluate the result, adjust the action and re-evaluate it again.